Ethanol and

isobutanol producer Gevo,

Inc. (GEVO: Nasdaq)

is installing equipment in its Luverne, Minnesota plant to improve efficiency

in corn processing. The company is

leasing a proprietary corn fractionation or slicing process developed Shockwave, LLC based

in DesMoines, Iowa. The new equipment is

intended to increase by-product output, including feed protein products and

food-grade corn oil. With sales of more

valuable by-products Gevo expects to improve overall profit margins. Shareholders can expect to see results after

the first quarter 2019, when the equipment installation is expected to be

complete.

Shockwave keeps

a low profile with no corporate website and no one to answer phone calls. However, there are plenty of other corn

fractionation companies that are worthy of investor scrutiny. The various technologies bring a higher level

of profitability to dry mill ethanol production by increasing efficiency in

corn feedstock utilization and creating new revenue streams. Another plus is a reduction in greenhouse gas

emissions.

Front-end corn

kernel fractionation is a new step for conventional ethanol dry-grind

production. Conventional ethanol plants

us a hammer or roller mill to grind whole corn kernels. The ground corn is missed with water and then

heated to break apart the starch polymers. Free glucose is freed from the corn starch and

then fermented into ethanol and carbon dioxide.

The non-starch portion is carried into a feed product called distillers

grains (DDGS).

It is not a very

efficient approach. Each bushel of corn

yields about 2.8 gallons of fuel ethanol and 17 pounds of DDGS. Corn is the largest expense for a dry grind

ethanol plant, leaving ethanol and chemical producers vulnerable to corn

prices.

Corn kernels

have three parts: germ, fiber and

endosperm. Fractionation before grinding

separates the three parts so that each can be used for its best attributes. The

germ is high in corn oil and its best suited as feedstock for biodiesel or even

as food-grade corn oil. The fiber or

bran is also removed, leaving the starchy part of the endosperm or grit for

fermentation into ethanol. Removal of

the germ and fiber before the grinding step affects ethanol yields because the

endosperm portion of the corn feedstock that heads to the fermentation step has

a higher concentration in starch. Then the non-fermentable portion of the

endosperm is turned into DDGS.

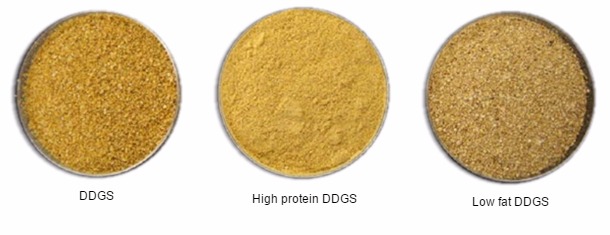

Fractionation

decreases the amount of DDGS by-products that have been a mainstay of ethanol

producers’ revenue streams. Those DDGS

also have lower fiber and oil content, but higher protein value. However, fractionation does lead to an even

higher-protein by-product that commands higher selling prices. The resulting high-protein grains stream or

HPGS has a wider market, including hog and poultry feed as well as ruminants. It

has similar composition to soy bean meal and is suitable for monogastric

animals. Thus even though DDGS has

represented as much as a quarter of ethanol producers profits in recent years,

the addition of HPGS is expected to deliver even higher sales and profits.

A study

described in an issue of Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology determined that

return on investment in front-end corn fractionation equipment increased by 2%

on a hypothetical 40-million-gallon per year plant. Increased ethanol production and new higher

protein DDGS by-products help to offset hefty capital costs associated with

the additional equipment. It also

provides an opportunity for Gevo and other ethanol producers to break into

different animal feed markets.

Bio-Process Group based in Indiana is a self-described engineering solutions company.

Among other processes for natural fibers, the company offers its Modular High

Value (MHV) biorefining system for corn ethanol production. The system integrates fractionation,

separation, fermentation and conversion technologies.

Oil seeds of all

kinds are the specialty of Crown Iron Works headquartered in

Minnesota. It claims to be the largest producer in North America of equipment

used in oil seed preparation, processing and refining. Crown’s corn fractionation process begins

with a tempering step that enables the corn kernels to absorb enough moisture

for the fracturing step. The process

focuses on the starchy endosperm or grit part of the kernel, sending that off

to the fermentation process at the ethanol plant. The germ is then converted into high protein

animal feed or edible oil.

In case anyone has

missed the point, ethanol producers are keen on maximizing the amount of pure fermentable

starch from their corn feedstock purchases.

Cereal Process

Technologies, LLC makes this concept the core marketing

message for its corn fractionation equipment.

CPT claims its system leads to purer germ and bran streams that command

higher prices in the market for ethanol production by-products. Another point

in their pitch to ethanol producers is lower energy costs since corn components

that cannot be turned into ethanol are not put through the fermentation

process.

No doubt there

are other sources for corn fractionation equipment. Most likely those sources of private held

just like the three mentioned here.

Perhaps the most important takeaway here is the need for ethanol

producers to adopt processes to make their plants more efficient. For price-taking competitive industry, cost

reduction and efficiency are keys to success.

Investors may be

hearing more about investment in operational efficiencies by ethanol products. More than 80% of corn ethanol plants in the

U.S. are dry grind and they are all under pressure to maximize profits. Gevo has not yet achieved sufficient scale to

deliver profits from its ethanol and isobutanol products. The company reported a 60% operating loss in

the twelve months ending June 2018.

However, the corn fractionation equipment can help move the needle to

that end. The unique lease agreement

with the elusive Shockwave equipment supplier means Gevo can also conserve its

capital resources. Gevo had $27 million

in cash on its balance sheet at the end of June 2018, but needs at least $1.25

million per month in cash to keep operations going.

Neither the author of the Small Cap Strategist web

log, Crystal Equity Research nor its affiliates have a beneficial interest in

the companies mentioned herein.

No comments:

Post a Comment